What is Python?

Python is an interpreted, interactive object-oriented programming language; it incorporated modules, classes, exceptions, dynamic typing and high level data types. Python is also powerful when it comes to clear syntax. It is a high-level general-purpose programming language that can be applied to many different classes of problems — with a large standard library that encapsulates string processing (regular expressions, Unicode, calculating differences between files), Internet protocols (HTTP, FTP, SMTP, XML-RPC, POP, IMAP, CGI programming), software engineering (unit testing, logging, profiling, parsing Python code), and operating system interfaces (system calls, filesystems, TCP/IP sockets). Here are some of Python’s features:

- An interpreted (as opposed to compiled) language. Contrary to C, for example, Python code does not need to be compiled before executing it. In addition, Python can be used interactively: many Python interpreters are available, from which commands and scripts can be executed.

- A free software released under an open-source license: Python can be used and distributed free of charge, even for building commercial software.

- Multi-platform: Python is available for all major operating systems, Windows, Linux/Unix, MacOS X, most likely your mobile phone OS, etc.

- A very readable language with clear non-verbose syntax

- A language for which a large variety of high-quality packages are available for various applications, from web frameworks to scientific computing.

- A language very easy to interface with other languages, in particular C and C++.

- Some other features of the language are illustrated just below. For example, Python is an object-oriented language, with dynamic typing (an object’s type can change during the course of a program).

What does it mean to be an object-oriented language?

Python is a multi-paradigm programming language. Meaning, it supports different programming approach. One of the popular approach to solve a programming problem is by creating objects. This is known as Object-Oriented Programming (OOP).

An object has two characteristics:

1) attributes

2) behavior

Let’s take an example:

Dog is an object:

a) name, age, color are data

b) singing, dancing are behavior

We call data as attributes and behavior as methods in object oriented programming. Again:

Data → Attributes & Behavior → Methods

The concept of OOP in Python focuses on creating reusable code. This concept is also known as DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself). In Python, the concept of OOP follows some basic principles:

Inheritance — A process of using details from a new class without modifying existing class.

Encapsulation — Hiding the private details of a class from other objects.

Polymorphism — A concept of using common operation in different ways for different data input.

Class

A class is a blueprint for the object.

We can think of class as an sketch of a dog with labels. It contains all the details about the name, colors, size etc. Based on these descriptions, we can study about the dog. Here, dog is an object.

The example for class of dog can be :

class Dog:

pass

Here, we use class keyword to define an empty class Dog. From class, we construct instances. An instance is a specific object created from a particular class.

A Class is the blueprint from which individual objects are created. In the real world we often find many objects with all the same type. Like cars. All the same make and model (have an engine, wheels, doors, …). Each car was built from the same set of blueprints and has the same components.

Object

Think of an object in Python as a block of memory, and a variable is just something that points/references to that block of memory. All the information relevant to your data is stored within the object itself. And the variable stores the address to that object. So it actually doesn’t matter if you reassign a variable pointing to an integer to point to a different data type.

>>> a = 1 >>> a = "I am a string now" >>> print(a) I am a string now

Every object has its own identity/ID that stores its address in memory. Every object has a type. An object can also hold references to other objects. For example, an integer will not have references to other objects but if the object is a list, it will contain references to each object within this list. We will touch up on this when we look at tuples later.

The built-in function id() will return an object’s id and type() will return an object’s type:

>>> list_1 = [1, 2, 3]

# to access this object's value >>> list_1 [1, 2, 3]

# to access this object's ID >>> id(list_1) 140705683311624

# to access object's data type >>> type(list_1) <class 'list'>

So, an object (instance) is an instantiation of a class. When class is defined, only the description for the object is defined. Therefore, no memory or storage is allocated.

The example for object of class Dog can be:

obj = Dog()

Here, obj is object of class Dog.

Suppose we have details of Dog. Now, we are going to show how to build the class and objects of Dog.

class Dog:

#class attribute

species = "animal"

# instance attribute

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

# instantiate the Dog class

blu = Dog("Blu", 10)

woo = Dog("Woo", 15)

# access the class attributes

print("Blu is an {}".format(blu.__class__.species))

print("Woo is also an {}".format(woo.__class__.species))

# access the instance attributes

print("{} is {} years old".format( blu.name, blu.age))

print("{} is {} years old".format( woo.name, woo.age))

When we run the program, the output will be:

Blu is an animal Woo is also an animal Blu is 10 years old Woo is 15 years old

In the above program, we create a class with name Dog. Then, we define attributes. The attributes are a characteristic of an object.

Then, we create instances of the Dog class. Here, blu and woo are references (value) to our new objects.

Then, we access the class attribute using __class __.species. Class attributes are same for all instances of a class. Similarly, we access the instance attributes using blu.name and blu.age. However, instance attributes are different for every instance of a class.

Let’s try to understand how value and identity are affected if you use operators “==” and “is”

The “==” operator compares values whereas “is” operator compares identities. Hence, a is b is similar to id(a) == id(y), but two different objects may share the same value, but they will never share the same identity.

Example:

>>> a = ['blu', 'woof'] >>> id(a) 1877152401480 >>> b = a >>> id(b) 1877152401480 >>> id(a) == id(b) True >>> a is b True >>> c = ['blu', 'woof'] >>> a == c True >>> id(c) 1877152432200 >>> id(a) == id(c) False

Hashability

What is a hash?

A hash is an integer that depends on an object’s value, and objects with the same value always have the same hash. (Objects with different values will occasionally have the same hash too. This is called a hash collision.) While id() will return an integer based on an object’s identity, the hash() function will return an integer (the object’s hash) based on the hashable object’s value:

>>> a = ('cow', 'bull')

>>> b = ('cow', 'bull')

>>> a == b

True

>>> a is b

False

>>> hash(a)

6950940451664727300

>>> hash(b)

6950940451664727300

>>> hash(a) == hash(b)

True

Immutable objects can be hashable, mutable objects can’t be hashable.This is important to know, because (for reasons beyond the scope of this post) only hashable objects can be used as keys in a dictionary or as items in a set. Since hashes are based on values and only immutable objects can be hashable, this means that hashes will never change during the object’s lifetime.

Hashability will be covered more under the mutable vs immutable object section, as sometimes a tuple can be mutable and how does that change values and understanding of mutable objects and immutable objects.

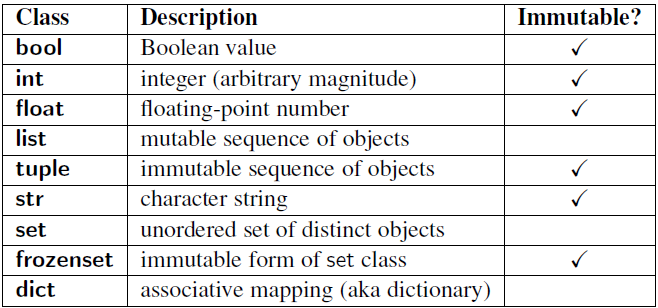

To summarize, EVERYTHING is an object in Python the only difference is some are mutable and some immutable. Wait but what kind of objects are possible in Python and which ones are mutable and which ones aren’t?

Objects of built-in types like (bytes, int, float, bool, str, tuple, unicode, complex) are immutable. Objects of built-in types like (list, set, dict, array, bytearray) are mutable. Custom classes are mutable. To simulate immutability in a class, one should override attribute setting and deletion to raise exceptions.

Now how would a newbie know which variables are mutable objects and which ones are not? For this we use 2 very handy built-in functions called id() and type()

What is id() and type()?

Syntax to use id()

id(object)

As we can see the function accepts a single parameter and is used to return the identity of an object. This identity has to be unique and constant for this object during the lifetime. Two objects with non-overlapping lifetimes may have the same id() value. If we relate this to C, then they are actually the memory address, here in Python it is the unique id. This function is generally used internally in Python.

Examples:

The output is the identity of the object passed. This is random but when running in the same program, it generates unique and same identity.

Input : id(2507) Output : 140365829447504 Output varies with different runs

Input : id("Holberton")

Output : 139793848214784

What is an Alias?

>>> a = 1 >>> id(a) 1904391232 >>> b = a #aliasing a >>> id(b) 1904391232 >>> b 1

An alias is a second name for a piece of data. Programmers use/ create aliases because it’s often easier and faster to refer data than to copy it. If the data that is being created and assigned is immutable then aliasing does not matter as the data won’t change, but there will be a lot of bugs if the data is mutable as it will lead to some issues like see below —

>>> a = 1 >>> id(a) 1904391232 >>> b = a #aliasing a >>> id(b) 1904391232 >>> b 1 >>> a = 2 >>> id(2) 1904391264 >>> id(b) 1904391232 >>> b 1 >>> a 2

as it can be seen a now points to 2 and id is different as compared to b which is still pointing to 1. In Python, aliasing happens whenever one variable’s value is assigned to another variable, because variables are just names that store references to values.

type() method returns class type of the argument(object) passed as parameter. type() function is mostly used for debugging purposes.

Two different types of arguments can be passed to type() function, single and three argument. If single argument type(obj) is passed, it returns the type of given object.

Syntax :

type(object)

We can find out what class an object belongs to using the built-in type()function:

>>> Blue = [1, 2, 3] >>> type(Blue) <class 'list'>

>>> def my_func(x) ... x = 89 >>> type(my_func) <class 'function'>

Now that we can compare variables to see their type and id’s, we can dive in deeper to understand how mutable and immutable objects work.

Mutable Objects vs. Immutable Objects

Not all Python objects handle changes the same way. Some objects are mutable, meaning they can be altered. Others are immutable; they cannot be changed but rather return new objects when attempting to update. What does this mean when writing Python code?

The following are some mutable objects:

- list

- dict

- set

- bytearray

- user-defined classes (unless specifically made immutable)

The following are some immutable objects:

- int

- float

- decimal

- complex

- bool

- string

- tuple

- range

- frozenset

- bytes

The distinction is rather simple: mutable objects can change, whereas immutable objects cannot. Immutable literally means not mutable.

A standard example are tuple and list: A tuple is filled on creation, and then is frozen – its content cannot change anymore. To a list, one can append elements, set elements and delete elements at any time. Although keep in mind exceptions: tuple is an immutable list whereas frozenset is an immutable set. Quoting stackoverflow answer-Tuples are indeed an ordered collection of objects, but they can contain duplicates and unhashable objects, and have slice functionality frozensets aren’t indexed, but you have the functionality of sets – O(1) element lookups, and functionality such as unions and intersections. They also can’t contain duplicates, like their mutable counterparts.

Let’s create a dictionary with immutable objects for keys —

>>> a = {‘blu’: 42, True: ‘woof’, (‘x’, ‘y’, ‘z’): [‘hello’]}

>>> a.keys()

dict_keys([‘blu’, True, (‘x’, ‘y’, ‘z’)])

As seen above keys in a are immutable, hashable objects, but if you try to call hash() on a mutable object(such as sets), or trying to use a mutable object for a dictionary key, an error will be raised:

>>> spam = {['hello', 'world']: 42}

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unhashable type: 'list'

>>> d = {'a': 1}

>>> spam = {d: 42}

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unhashable type: 'dict'

So, tuples, being immutable objects, can be used as dictionary keys?

>>> spam = {('a', 'b', 'c'): 'hello'}

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unhashable type: 'list'

As seen above, if a tuple contains a mutable object, according to the previous explanation about hashability it cannot be hashed. So, immutable objects can be hashable, but this doesn’t necessarily mean they’re alwayshashable. And remember, the hash is derived from the object’s value.

This is an interesting corner case: a tuple (which should be immutable) that contains a mutable list cannot be hashed. This is because the hash of the tuple depends on the tuple’s value, but if that list’s value can change, that means the tuple’s value can change and therefore the hash can change during the tuple’s lifetime.

So far it is now understood that some tuples are hashable — immutable but some other tuple are not hashable — mutable. According to official Python documentation immutable and mutable are defined as — “An object with a fixed value” and “Mutable objects can change their value”. This can possibly mean that mutability is a property of objects, hence it makes sense that some tuples will be mutable while others won’t be.

>>> a = ('dogs', 'cats', [1, 2, 3])

>>> b = ('dogs', 'cats', [1, 2, 3])

>>> a == b

True

>>> a is b

False

>>> a[2].append(99)

>>> a

('dogs', 'cats', [1, 2, 3, 99])

>>> a == b

False

In this example, the tuples a and b have equal (==) values but are different objects, so when list is changed in tuple a the values get changed as a is not longer == b and did not change values of b. This example states that tuples are mutable.

While Python tends towards mutability, there are many use-cases for immutability as well. Here are some straightforward ones:

- Mutable objects are great for efficiently passing around data. Let’s say object

antonandbertahave access to the samelist.antonadds“lemons”to the list, andbertaautomatically has access to this information.

If both would use atuple, anton would have to copy the entries of his shopping-tuple, add the new element, create a new tuple, then send that toberta. Even if both can talk directly, that is a lot of work. - Immutable objects are great for working with the data. So

bertais going to buy all that stuff – she can read everything, make a plan, and does not have to double check for changes. If next week, she needs to buy more stuff for the same shopping-tuple,bertajust reuses the old plan. She has the guarantee thatantoncannot change anything unnoticed.

If both would use alist,bertacould not plan ahead. She has no guarantee that“lemons”are still on the list when she arrives at the shop. She has no guarantee that next week, she can just repeat what was appropriate last week.

You should generally use mutable objects when having to deal with growing data. For example, when parsing a file, you may append information from each line to a list. Custom objects are usually mutable, buffering data, adjusting to new conditions and so on. In general, whenever something can change, mutable objects are much easier.

Immutable objects are sparingly used in python — usually, it is implicit such as using int or other basic, immutable types. Often, you will be using mutable types as de-facto immutable – many lists are filled at construction and never changed. There is also no immutable dict. You should enforce immutability to optimise algorithms, e.g. to do caching.

Interestingly enough, python’s often-used dict requires keys to be immutable. It is a data structure that cannot work with mutable objects, since it relies on some features being guaranteed for its elements.

Mutable example

>>> my_list = [10, 20, 30] >>> print(my_list)

[10, 20, 30]

>>> my_list = [10, 20, 30] >>> my_list[0] = 40 >>> print(my_list)

[40, 20, 30]

Immutable example

>>> tuple_ = (10, 20, 30) >>> print(tuple_)

[10, 20, 30]

>>> tuple_ = [10, 20, 30] >>> tuple_[0] = 40 >>> print(tuple_)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "test.py", line 3, in < module >

my_yuple[0] = 40

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

If you want to write most efficient code, you should be the knowing difference between mutable and immutable in python. Concatenating string in loops wastes lots of memory , because strings are immutable, concatenating two strings together actually creates a third string which is the combination of the previous two. If you are iterating a lot and building a large string, you will waste a lot of memory creating and throwing away objects. Use list compression join technique.

Python handles mutable and immutable objects differently. Immutable are quicker to access than mutable objects. Also, immutable objects are fundamentally expensive to “change”, because doing so involves creating a copy. Changing mutable objects is cheap.

Interning, integer caching and everything called: NSMALLPOSINTS & NSMALLNEGINTS

Easy things first —

NSMALLNEGINTS is in the range -5 to 0 and NSMALLPOSINTS is in the 0 to 256 range. These are macros defined in Python — earlier versions ranged from -1 to 99, then -5 to 99 and finally -5 to 256. Python keeps an array of integer objects for “all integers between -5 and 256”. When creating an int in that range, it is actually just getting a reference to the existing object in memory.

If x = 42, what happens actually is Python performing a search in the integer block for the value in the range -5 to 256. Once x falls out of the scope of this range, it will be garbage collected (destroyed) and be an entirely different object. The process of creating a new integer object and then destroying it immediately creates a lot of useless calculation cycles, so Python preallocated a range of commonly used integers.

There are exception to immutable objects as stated above by making a tuple “mutable”. As it is known a new object is created each time a variable makes a reference to it, it does happen slightly differently for a few things –

a) Strings without whitespaces and less than 20 characters

b) Integers between -5 to 256 (including both as explained above)

c) empty immutable objects (tuples)

These objects are always reused or interned. This is due memory optimization in Python implementation. The rationale behind doing this is as follows:

- Since programmers use these objects frequently, interning existing objects saves memory.

- Since immutable objects like tuples and strings cannot be modified, there is no risk in interning the same object.

So what does it mean by “interning”?

interning allows two variables to refer to the same string object. Python automatically does this, although the exact rules remain fuzzy. One can also forcibly intern strings by calling the intern()function. Guillo’s articleprovides an in-depth look into string interning.

Example of string interning with more than 20 characters or whitespace will be new objects:

>>> a = "Howdy! How are you?" >>> b = "Howdy! How are you?" >>> a is b False

but, if a string is less than 20 char and no whitespace it will look somewhat like this:

>>> a = "python" >>> b = "python" >>> a is b True

As a and b refer to the same objects.

Let’s move on to integers now.

As explained above in macro definition integer caching is happening because of preload python definition of commonly used integers. Hence, variables referring to an integer within the range would be pointing to the same object that already exists in memory:

>>> a = 256 >>> b = 256 >>> a is b True

This is not the case if the object referred to is outside the range:

>>> a = 1024 >>> b = 1024 >>> a is b False

Lastly, let’s talk about empty immutable objects:

>>> a = () >>> b = () >>> a is b True

Here a and b refer to the same object in memory as it is an empty tuple, but this changes if the tuple is not empty.

>>> a = (1, 2) >>> b = (1, 2) >>> a == b True >>> a is b False

Passing mutable and immutable objects into functions:

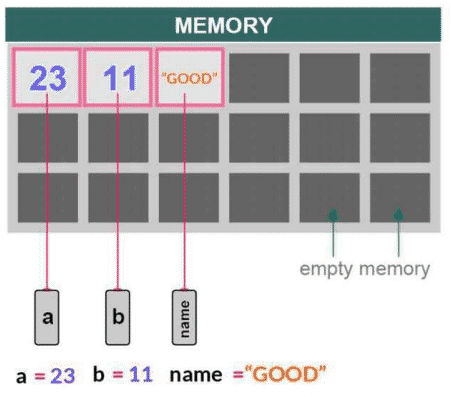

Immutable and mutable objects or variables are handled differently while working with function arguments. In the following diagram, variables a, band name point to their memory locations where the actual value of the object is stored.

Major Concepts of Function Argument Passing in Python

Arguments are always passed to functions by object in Python. The caller and the function code blocks share the same object or variable. When we change the value of a function argument inside the function code block scope, the value of that variable also changes inside the caller code block scope regardless of the name of the argument or variable. This concept behaves differently for both mutable and immutable arguments in Python.

In Python, integer, float, string and tuple are immutable objects. list, dict and set fall in the mutable object category. This means the value of integer, float, string or tuple is not changed in the calling block if their value is changed inside the function or method block but the value of list, dict or set object is changed.

Python Immutable Function Arguments

Python immutable objects, such as numbers, tuple and strings, are also passed by reference like mutable objects, such as list, set and dict. Due to state of immutable (unchangeable) objects if an integer or string value is changed inside the function block then it much behaves like an object copying. A local new duplicate copy of the caller object inside the function block scope is created and manipulated. The caller object will remain unchanged. Therefore, caller block will not notice any changes made inside the function block scope to the immutable object. Let’s take a look at the following example.

Python Immutable Function Argument — Example and Explanation

def foo1(a):

# function block

a += 1

print(‘id of a:’, id(a)) # id of y and a are same

return a

# main or caller block x = 10 y = foo1(x)

# value of x is unchanged print(‘x:’, x)

# value of y is the return value of the function foo1

# after adding 1 to argument ‘a’ which is actual variable ‘x’ print(‘y:’, y) print(‘id of x:’, id(x)) # id of x print(‘id of y:’, id(y)) # id of y, different from x

Result:

id of a: 1456621360

x: 10

y: 11

id of x: 1456621344

id of y: 1456621360

Explanation:

- Original object integer

xis immutable (unchangeable). A new local duplicate copyaof the integer objectxis created and used inside the functionfoo1()because integers are immutable objects and can’t be changed in placed. The caller main block where variablexis created has no effect on the value of the variablex. - The value of variable

yis the value of variableareturned from functionfoo1()after adding1. - Variable

xandyare different as you can see their id values are different. - Variable

yandaare same as you can see their id values are same. Both point to same integer object.

Python Mutable Function Arguments

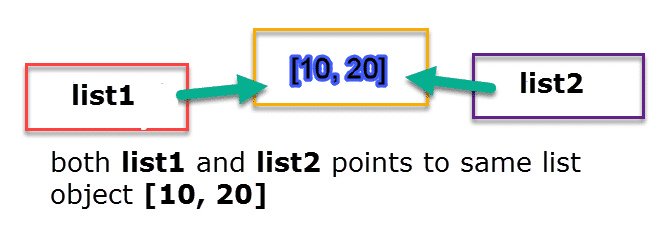

Python mutable objects like dict and list are also passed by reference. If the value of a mutable object is changed inside the function block scope then its value is also changed inside the caller or main block scope regardless of the name of the argument. Let’s take a look at the following diagram and code example with the explanation at the end when we assign list1 = list2.

Python Mutable Function Argument — Example and Explanation

def foo2(func_list):

# function block func_list.append(30) # append an element

def foo3(func_list):

# function block del func_list[1] # delete 2nd element def foo4(func_list):

# function block func_list[0] = 100 # change value of 1st element

# main or caller block list1 = [10, 20] list2 = list1 # list1 and list2 point to same list object print(‘original list:’, list1) print(‘list1 id:’, id(list1)) print(‘value of list2:’, list2) print(‘list2 id:’, id(list2))

foo2(list1)

print(‘nafter foo2():’, list1) print(‘list1 id:’, id(list1)) print(‘value of list2:’, list2) print(‘list2 id:’, id(list2))

foo3(list1)

print(‘nafter foo3():’, list1) print(‘list1 id:’, id(list1)) print(‘value of list2:’, list2) print(‘list2 id:’, id(list2))

foo4(list1)

print(‘nafter foo4():’, list1) print(‘list1 id:’, id(list1)) print(‘value of list2:’, list2) print(‘list2 id:’, id(list2))

Result:

original list: [10, 20]list1 id: 24710360value of list2: [10, 20]list2 id: 24710360

after foo2(): [10, 20, 30]list1 id: 24710360value of list2: [10, 20, 30]list2 id: 24710360

after foo3(): [10, 30]list1 id: 24710360value of list2: [10, 30]list2 id: 24710360

after foo4(): [100, 30]list1 id: 24710360value of list2: [100, 30]list2 id: 24710360

Explanation:

- We have created a list object

list1and assigned same object to a new variablelist2. Now bothlist1andlist2points to the same memory where actual list object[10, 20]is stored. - We passed the value

list1variable into the function argumentfunc_list. We appended, deleted and modified thelist1object element in functionfoo2(),foo3()andfoo4()through argumentfunc_list. - As you have noticed that actual object

list1is changed in the main block when we changed its value in the function block. - You should also notice that the value of

list2variable also changes when the value oflist2changes. As we have also read, this is because bothlist1andlist2variable points to samelistobject[10, 20]. list1object ID doesn’t change after every call to functionfoo2(),foo3()andfoo4().This is becauselist1is mutable and can be modified. Therefore, changinglist1object modifies original object value and doesn’t create the new object.

This article was produced in partnership with Holberton School and originally appeared on Medium.