I’ve been a writer for more than 20 years. I’ve written thousands of articles and how-tos on various technical topics and have penned more than 40 works of fiction. So, the written word is not only important to me, it’s familiar to the point of being second nature. And through those two decades (and counting) I’ve done nearly all my work on the Linux platform. I must confess, during those early years it wasn’t always easy. Formats didn’t always mesh with what an editor required and, in some cases, the open source platform simply didn’t have the necessary tools required to get the job done.

That was then, this is now.

A perfect storm of Linux evolution and web-based tools have made it such that any writer can get the job done (and done well) on Linux. But what tools will you need? You might be surprised to find out that, in some instances, the job cannot be efficiently done with 100% open source tools. Even with that caveat, the job can be done. Let’s take a look at the tools I’ve been using as both a tech writer and author of fiction. I’m going to outline this by way of my writing process for both nonfiction and fiction (as the process is different and requires specific tools).

A word of warning to seriously hard-core Linux users. A long time ago, I gave up on using tools like LaTeX and DocBook for my writing. Why? Because, for me, the focus must be on the content, not the process. When you’re facing deadlines, efficiency must take precedent.

Nonfiction

We’ll start with nonfiction, as that process is the simpler of the two. For writing technical how-tos, I collaborate with different editors and, in some cases, have to copy/paste content into a CMS. But like with my fiction, the process always starts with Google Drive. This is the point at which many open source purists will check out. Fear not, you can always opt to either keep all of your files locally, or use a more open-friendly cloud service (such as Zoho or nextCloud).

Why start on the cloud? Over the years, I’ve found I need to be able to access that content from anywhere at any time. The simplest solution was to migrate the cloud. I’ve also become paranoid about losing work. To that end, I make use of a tool like Insync to keep my Google Drive in sync with my desktop. With that desktop sync in place, I know there’s always a backup of my work, in case something should go awry with Google Drive.

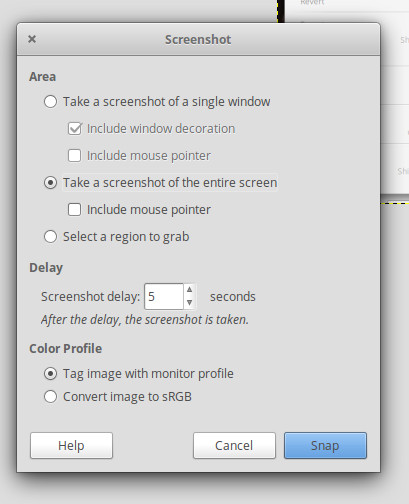

For those clients with whom I must enter content into a Content Management System (CMS), the process ends there. I can copy/paste directly from a Google Doc into the CMS and be done with it. Of course, with technical content, there are always screenshots involved. For that, I use Gimp, which makes taking screenshots simple:

-

Open Gimp.

-

Click File > Create > Screenshot.

-

Select from a single window, the entire screen, or a region to grab (Figure 1).

-

Click Snap.

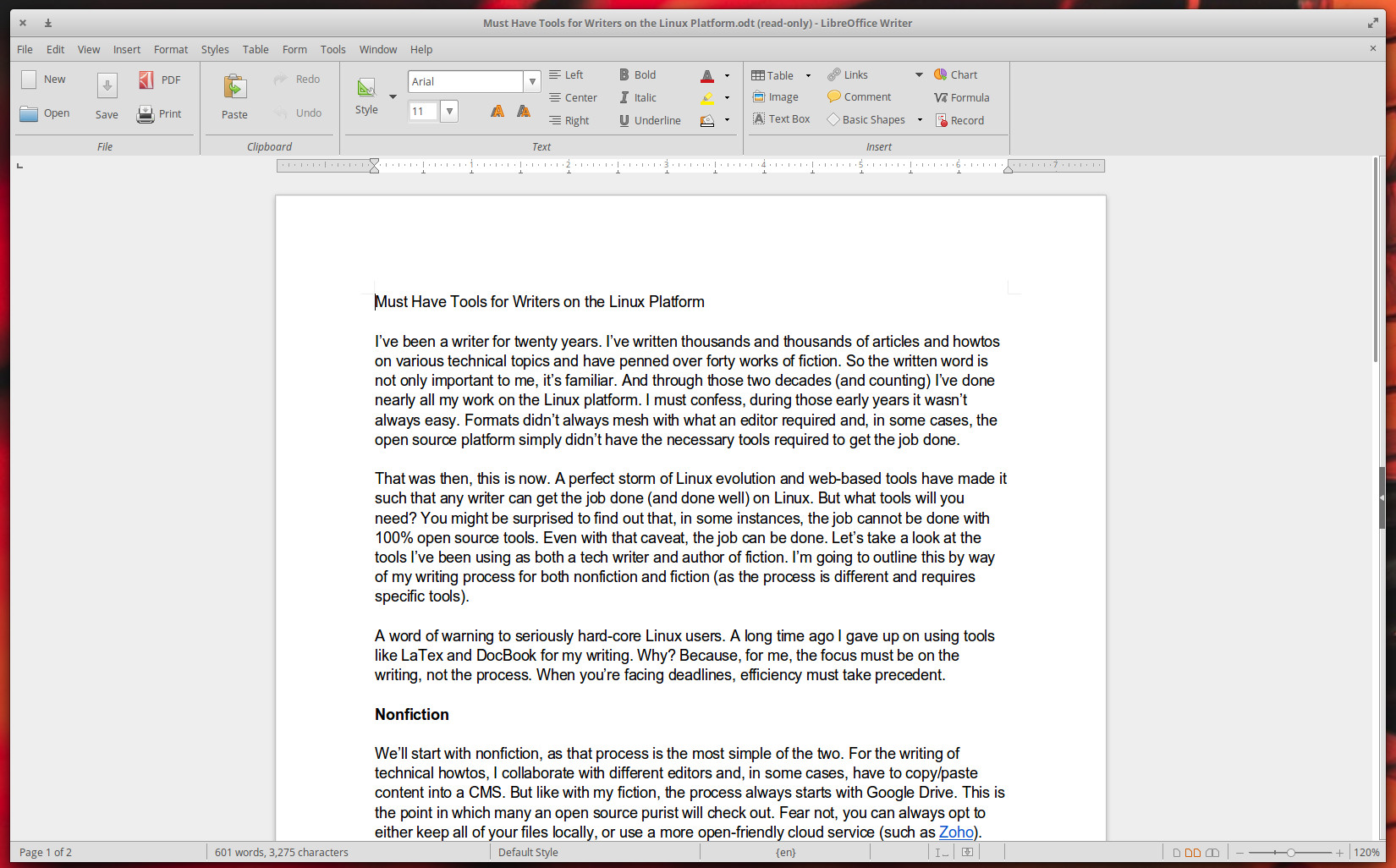

The majority of my clients tend to prefer I work with Google Docs, because I can share folders so that they have reliable access to the content. There are a few clients I have that do not work with Google Docs, and so I must download the files into a format that can be used. What I do for this is download in .odt format, open the document in LibreOffice (Figure 2), format as needed, save in a format required by the client, and send the document on.

And that, is the end of the line for nonfiction.

Fiction

This is where it gets a bit more complicated. The beginning steps are the same, as I always write every first draft of a novel in Google Docs. Once that is complete, I then download the file to my Linux desktop, open the file in LibreOffice, format as necessary, and then save as a file type supported by my editor (unfortunately, that means .docx).

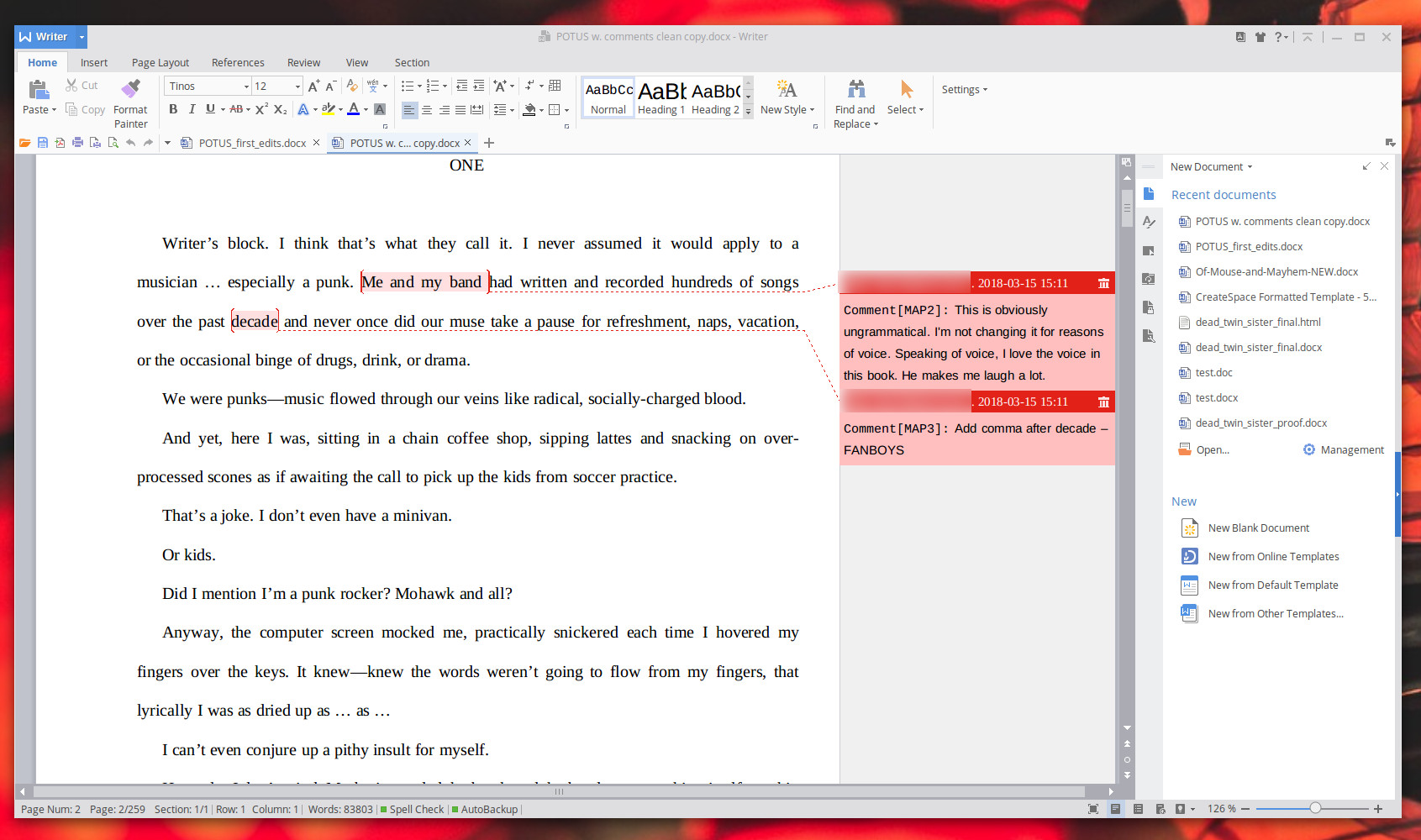

The next step in the process gets a bit dicey. My editor prefers to use comments over track changes (as it makes it easier for both of us to read the document as we make changes). Because of this, a 60k word doc can include hundreds upon hundreds of comments, which slows LibreOffice to a useless crawl. Once upon a time, you could up the memory used for documents, but as of LibreOffice 6, that is no longer possible. This means any larger, novel-length, document with numerous comments will become unusable. Because of that, I’ve had to take drastic measures and use WPS Office (Figure 3). Although this isn’t an open source solution, WPS Office does a fine job with numerous comments in a document, so there’s no need to deal with the frustration that is LibreOffice (when working with these large files with hundreds of comments).

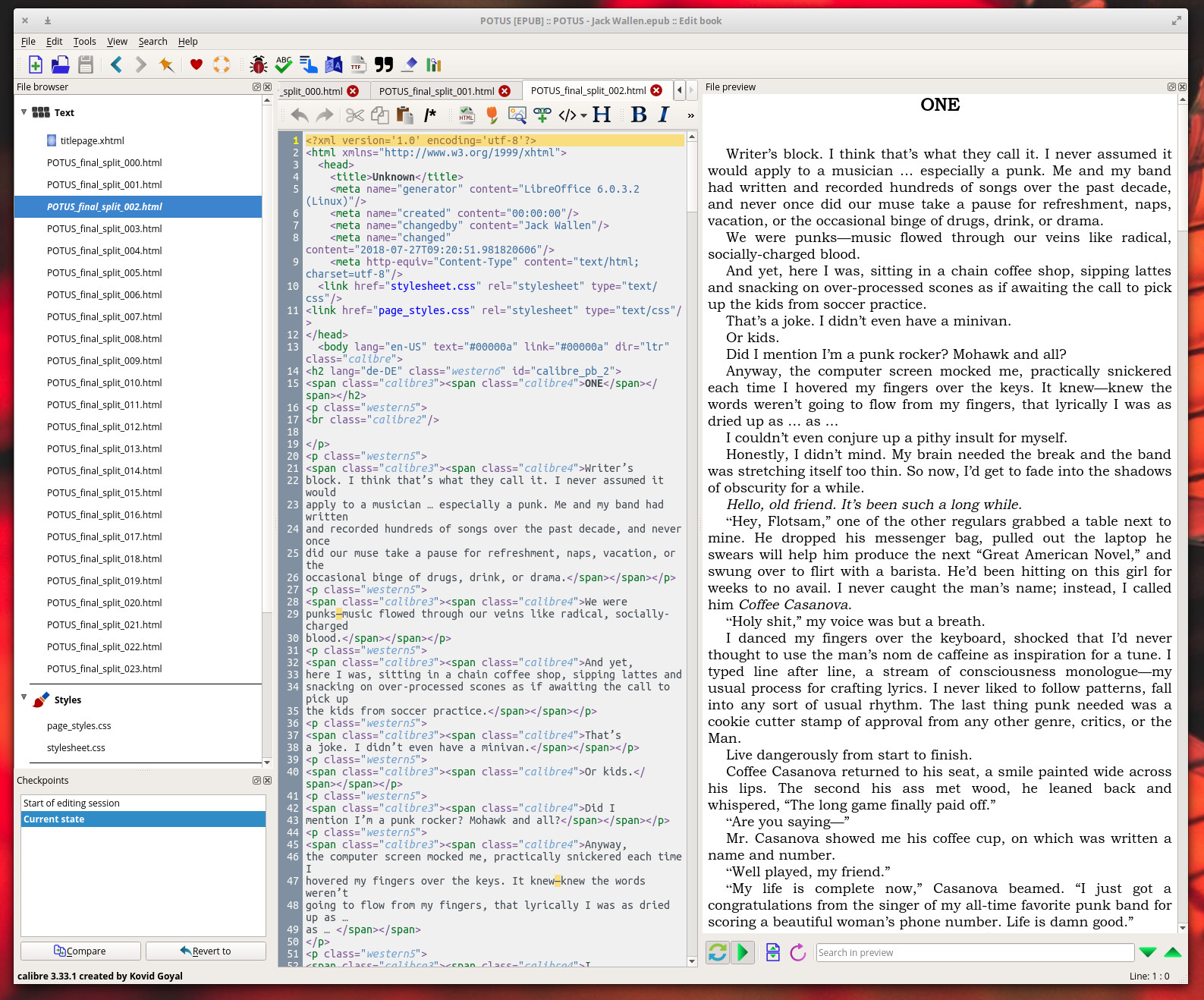

Once my editor and I finish up the edits for the book (and all comments have been removed), I can then open the file in LibreOffice for final formatting. When the formatting is complete, I save the file in .html format and then open the file in Calibre for exporting the file to .mobi and .epub formats.

Calibre is a must-have for anyone looking to publish on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Smashwords, or other platforms. One thing Calibre does better than other, similar, solutions is enable you to directly edit the .epub files (Figure 4). For the likes of Smashword, this is an absolute necessity (as the export process will add elements not accepted on the Smashwords conversion tool).

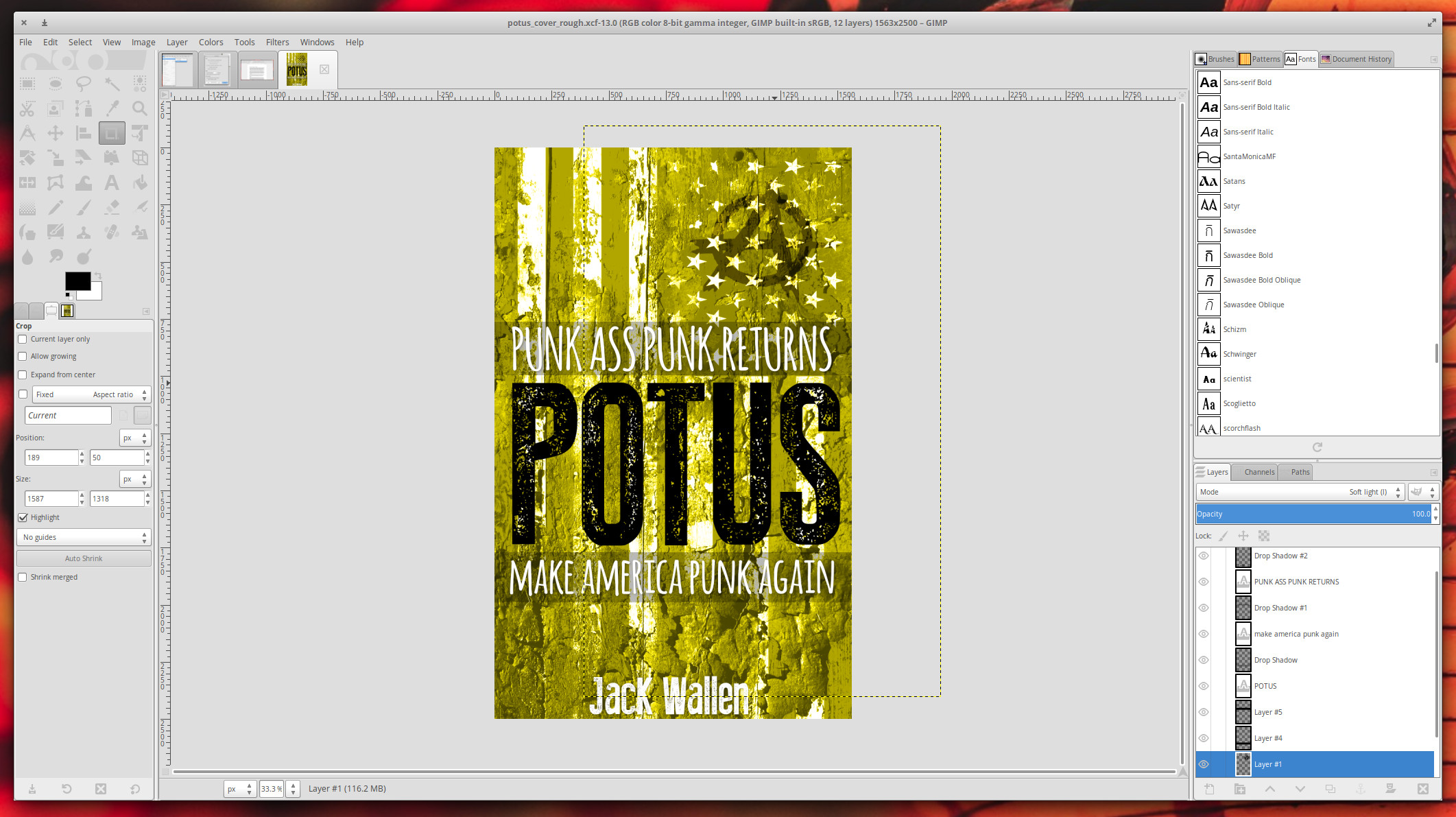

After the writing process is over (or sometimes while waiting for an editor to complete a pass), I’ll start working on the cover for the book. That task is handled completely in Gimp (Figure 5).

And that finishes up the process of creating a work of fiction on the Linux platform. Because of the length of the documents, and how some editors work, it can get a bit more complicated than the process of creating nonfiction, but it’s far from challenging. In fact, creating fiction on Linux is just as simple (and more reliable) than other platforms.

HTH

I hope this helps aspiring writers to have the confidence to write on the Linux platform. There are plenty of other tools available to use, but the ones I have listed here have served me quite well over the years. And although I do make use of a couple of proprietary tools, as long as they keep working well on Linux, I’m okay with that.

Learn more about Linux in the Introduction to Open Source Development, Git, and Linux (LFD201) training course from The Linux Foundation, and sign up now to start your open source journey.