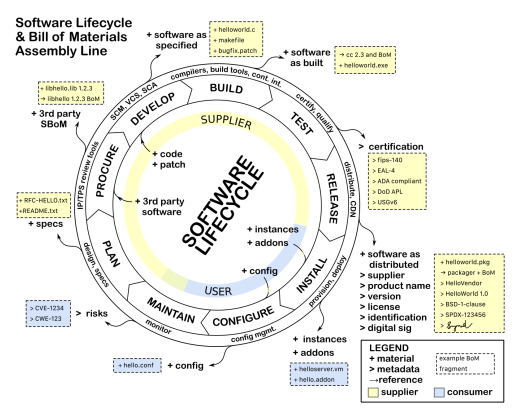

A software bill of materials (SBOM) is a way of summarizing key facts about the software on a system. At the heart of it, it describes the set of software components and the dependency relationships between these components that are connected together to make up a system.

Modern software today consists of modular components that get reused in different configurations. Components can consist of open source libraries, source code or other external, third-party developed software. This reuse lets innovation of new functionality flourish, especially as a large percentage of those components being connected together to form a system may be open source. Each of these components may have different limitations, support infrastructure, and quality levels. Some components may be obsolete versions with known defects or vulnerabilities. When software runs a critical safety system, such as life support, traffic control, fire suppression, chemical application, etc., being able to have full transparency about what software is part of a system is an essential first step for being able to do effective analysis for safety claims.

Why is this important?

When a system has functionality incorporated that could have serious consequences in terms of a person’s well being or significant loss, the details matter. The level of transparency and traceability may need to be at different levels of details based on the seriousness of the consequences.

Source: NTIA’s Survey of Existing SBOM Formats and Standards

What does this have to do with Safety Critical Development?

Safety Standards, and the claims necessarily made against them, come in a variety of different forms. The safety standards themselves mostly vary according to the industry that they target: Automotive uses ISO 26262, Aviation uses DO 178C for software and DO 254 for hardware, Industrial uses IEC 61508 or ISO 13849, Agriculture uses ISO 25119, and so on. From a software perspective, all of these standards work from the same premise that the full details of all software is known: The software should be developed according to a software quality perspective, with additional measures added for safety. In some instances these additional safety measures come in the form of a software FMEA (Failure Modes and Effects Analysis), but in all of them, there are specific code coverage metrics to demonstrate that as much of the code as possible has been tested and that the code complies with the requirements.

Another item that all safety standards have in common is the expectation that the system configuration is going to be managed as part of any product release. Configuration management (CM) is an inherent expectation in software already, but with safety this becomes even more crucial because of the need to track exactly what the configuration of a system (and its software) is if there is a subsequent incident in the field while the system is being used. From a software perspective, this means we need several things:

- The source code at the time of release

- The documentation associated with it

- The configuration used to build the software

- The specific versions of the tools used to build the software

The goal, then, is to be able to rebuild exactly what the executable or binary was at the time of release.

From the above, it is inherently obvious how the SBOM fits into the need for CM. The safety standards CM requirements, from a source code and configuration standpoint, are greatly simplified by following an effective SBOM process. An SBOM supports capturing the details of what is in a specific release and supports determining what went wrong if a failure occurs.

Because software often relies upon reusable software components written by someone other than the author of the main system/application, the safety standards also have a specific expectation and a given set of criteria for software that you end up including in your final product. This can be something as simple as a library of run-time functions as we might expect to see from a run-time library, to something as extensive as a middleware that manages communication between components. While the safety standards do not always require that the included software be developed in accordance with a safety standard, there are still expectations that you can prove that the software was developed at least in compliance with a quality management framework such that you can demonstrate that the software fulfills its requirements. This is still predicated on the condition that you know all of the details about the software component and that it fulfills its intended purpose.

The included software components can be from:

- Third parties

- Existing SW not developed according to a safety standard

- Internally developed software already in use

Regardless of the source or current usage of the software, the SBOM should describe all of the included software in the release.

To this end, the safety standards expect that the following is available for each software component included in your project:

- Unique ID, something to uniquely identify the version of the software you are using. Variations in releases make it important to be able to distinguish the exact version you are using. The unique ID could be as simple as using the hash from a configuration management tool, so that you know whether it has changed.

- Any safety requirements that might be violated if the included software performs incorrectly. This is specifically looking for failures in the included software that can cause the safety function to perform incorrectly. (This is referred to as a cascading failure.)

- Requirements for the software component

- This should include the results of any testing to demonstrate requirements coverage

- Coverage for nominal operating conditions and behavior in the case of failure

- For highly safety critical requirements, test coverage should be in accordance with what the specification expects (e.g., Modified Condition/Decision Coverage (MC/DC) level code coverage)

- The intended use of the software component

- The component’s build configuration (how it was built so that it can be duplicated in the future)

- Any required and provided interfaces and shared resources used by the software component. A component can add demand for system-level resources that might not be accounted for.

- Application manual (documentation)

- Instructions on how to integrate the software component correctly and invoke it properly

- What the software might do under anomalous operating conditions (e.g., low memory or low available CPU)

- Any chained dependencies that a component may require

- Any existing bugs and their workarounds

Conclusion

At a minimum, the SBOM describes the software component, supplier and version number, with an enumeration of the included dependent components. This is what is being called for in the minimum viable definition of an SBOM to support cyber security[1] or safety critical software[2].

Having a minimum level of information, while better than nothing, is not sufficient for the level of analysis that safety claims expect. Knowing exactly which source files were included in the build is a better starting point. Even better still is knowing the configuration options that were used to create the image (and be able to reproduce it), and being able to check via some form of integrity check (like a hash) that the built components haven’t changed is going to be key to having a sound foundation for the safety case. SBOMs need to scale from the minimum, to the level of detail necessary to satisfy the safety analysis.

While SBOM tooling may not be able to populate all of this information today, the tools are continuing to evolve so that the facts necessary to support safety analysis can be made available. An international open SBOM standard, like SPDX[3] can become the baseline for modern configuration management and effective documentation of safety critical systems.

[1] The Minimum Elements For a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) from NTIA

[2] ISO 26262:2018, Part 8, Clause 12 – Qualification of Software Components

[3] ISO/IEC 5962:2021 – Information technology — SPDX® Specification V2.2.1

Authors

Peter Brink, Functional Safety Engineering Leader, kVA by UL, Underwriters Laboratories (UL)

Kate Stewart, VP Dependable Embedded Systems, The Linux Foundation