This is the third article in our series on migrating to Linux. If you missed earlier articles, they provided an introduction to Linux for new users and an overview of Linux files and filesystems. In this article, we’ll discuss graphical environments. One of the advantages of Linux is that you have lots of choices, and you can select a graphical interface and customize it to work just the way you like it.

Some of the popular graphical environments in Linux include: Cinnamon, Gnome, KDE Plasma, Xfce, and MATE, but there are many options.

One thing that is often confusing to new Linux users is that, although specific Linux distributions have a default graphical environment, usually you can change the graphical interface at any time. This is different from what people are used to with Windows and Mac OS. The distribution and the graphical environment are separate things, and in many cases, they aren’t tightly coupled together. Additionally, you can run applications built for one graphical environment inside other graphical environments. For example, an application built for the KDE Plasma graphical interface will typically run just fine in the Gnome desktop graphical environment.

Some Linux graphical environments try to mimic Microsoft Windows or Apple’s MacOS to a degree because that’s what some people are familiar with, but other graphical interfaces are unique.

Below, I’ll cover several options showcasing different graphical environments running on different distributions. If you are unsure about which distribution to go with, I recommend starting with Ubuntu. Get the Long Term Support (LTS) version (which is 16.04.3 at the time of writing). Ubuntu is very stable and easy to use.

Transitioning from Mac

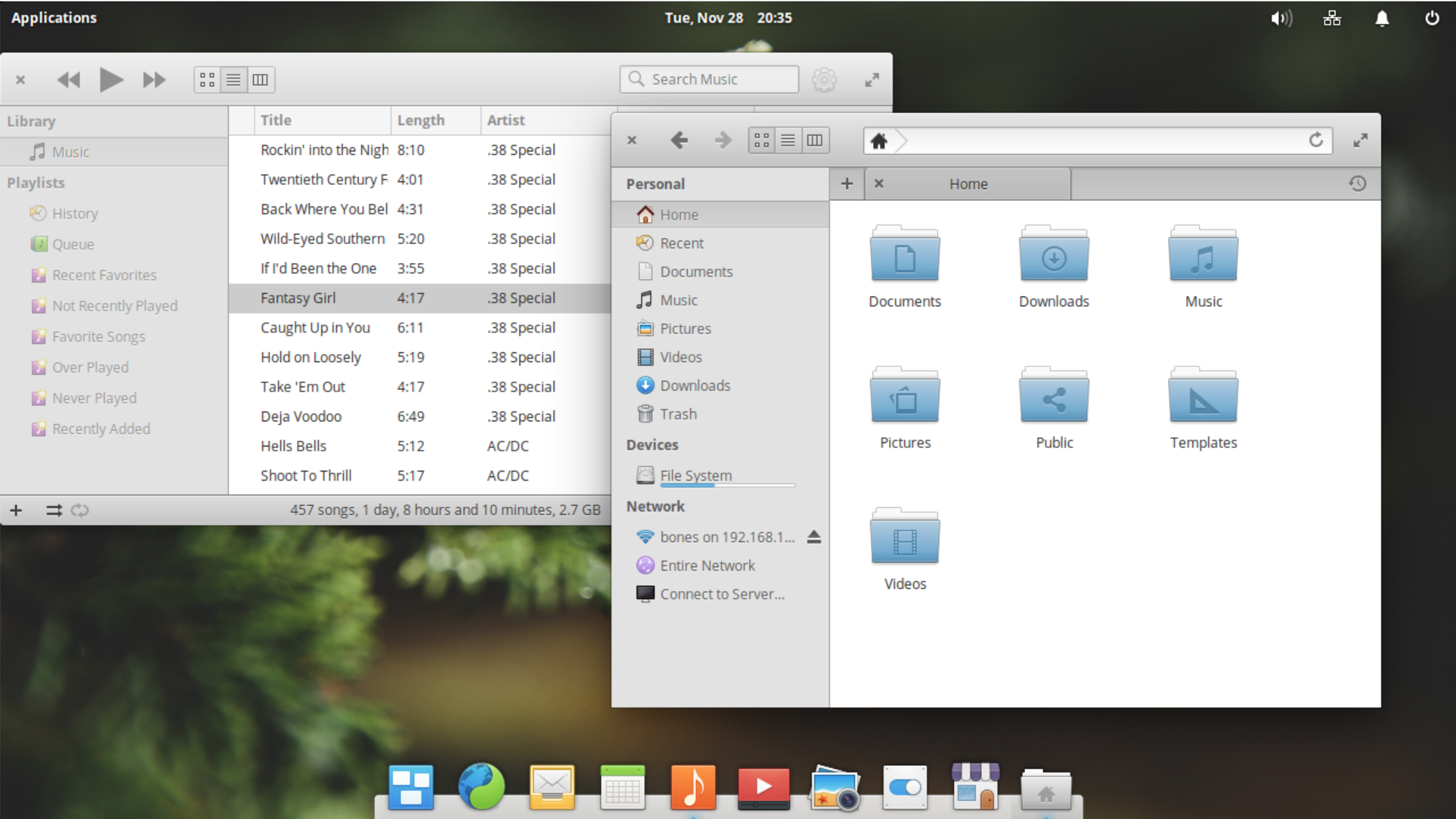

The Elementary OS distribution provides a very Mac-like interface. It’s default graphical environment is called Pantheon, and it makes transitioning from a Mac easy. It has a dock at the bottom of the screen and is designed to be extremely simple to use. In its aim to keep things simple, many of the default apps don’t even have menus. Instead, there are buttons and controls on the title bar of the application (Figure 1).

The Ubuntu distribution presents a default graphical interface that is also very Mac like. Ubuntu 17.04 or older uses the graphical environment called Unity, which by default places the dock on the left side of the screen and has a global menu bar area at the top that is shared across all applications. Note that newer versions of Ubuntu are switching to the Gnome environment.

Transitioning from Windows

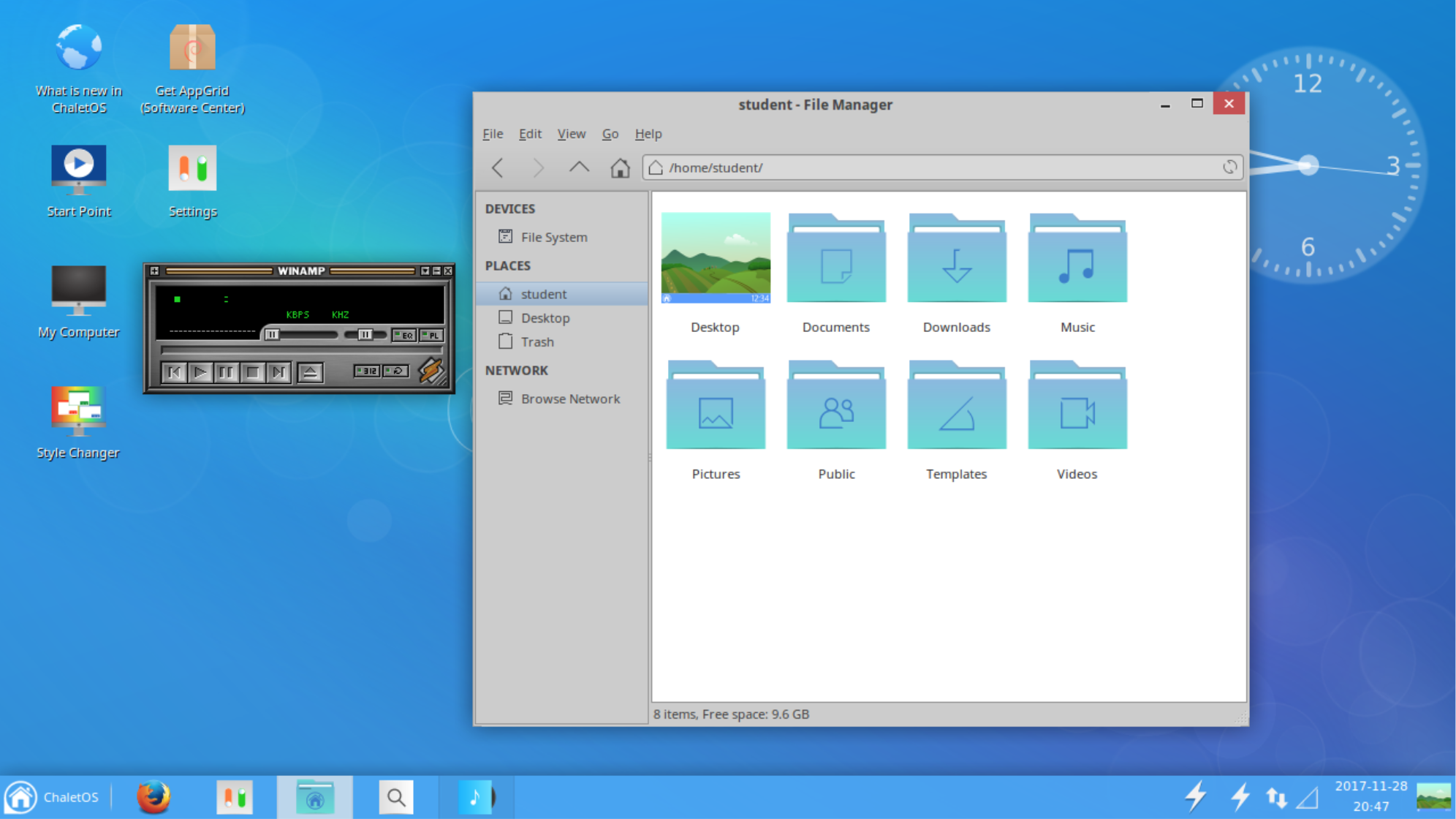

ChaletOS models its interface after Windows to help make migrating from Windows easier. ChaletOS used the graphical environment called Xfce (Figure 2). It has a home/start menu in the usual lower left corner of the screen with the search bar. There are desktop icons and notifications in the lower right corner. It looks so much like Windows that, at first glance, people may even assume you are running Windows.

The Zorin OS distribution also tries to mimic Windows. Zorin OS uses the Gnome desktop modified to work like Windows’ graphical interface. The start button is at the bottom left with the notification and indicator panel on the lower right. The start button brings up a Windows-like list of applications and a search bar to search.

Unique Environments

One of the most commonly used graphical environments for Linux is the Gnome desktop (Figure 3). Many distributions use Gnome as the default graphical environment. Gnome by default doesn’t try to be like Windows or MacOS but aims for elegance and ease of use in its own way.

The Cinnamon environment was created mostly out of a negative reaction to the Gnome desktop environment when it changed drastically from version 2 to version 3. Although Cinnamon doesn’t look like the older Gnome desktop version 2, it attempts to provide a simple interface, which functions somewhat similar to that of Windows XP.

The graphical environment called MATE is modeled directly after Gnome version 2, which has a menu bar at the top of the screen for applications and settings, and it presents a panel at the bottom of the screen for running application tabs and other widgets.

The KDE plasma environment is built around a widget interface where widgets can be installed on the desktop or in a panel (Figure 4).

No graphical environment is better than another. They’re just different to suit different people’s tastes. And again, if the options seem too much, start with Ubuntu.

Differences and Similarities

Different operating systems do some things differently, which can make the transition challenging. For example, menus may appear in different places and settings may use different paths to access options. Here I list a few things that are similar and different in Linux to help ease the adjustment.

Mouse

The mouse often works differently in Linux than it does in Windows and MacOS. In Windows and Mac, you double-click on most things to open them up. In Linux, many Linux graphical interfaces are set so that you single click on the item to open it.

Also in Windows, you usually have to click on a window to make it the focused window. In Linux, many interfaces are set so that the focus window is the one under the mouse, even if it’s not on top. The difference can be subtle, and sometimes the behavior is surprising. For example, in Windows if you have a background application (not the top window) and you move the mouse over it, without clicking, and scroll the mouse wheel, the top application window will scroll. In Linux, the background window (the one with the mouse over it) will scroll instead.

Menus

Application menus are a staple of computer programs and recently there seems to be a movement to move the menus out of the way or to remove them altogether. So when migrating to Linux, you may not find menus where you expect. The application menu might be in a global shared menu bar like on MacOS. The menu might be below a “more options” icon, similar to those in many mobile applications. Or, the menu may be removed altogether in exchange for buttons, as with some of the apps in the Pantheon environment in Elementary OS.

Workspaces

Many Linux graphical environments present multiple workspaces. A workspace fills your entire screen and contains windows of some running applications. Switching to a different workspace will change which applications are visible. The concept is to group the open applications used for one project together on one workspace and those for another project on a different workspace.

Not everyone needs or even likes workspaces, but I mention these because sometimes, as a newcomer, you might accidentally switch workspaces with a key combination, and go, “Hey! where’d my applications go?” If all you see is the desktop wallpaper image where you expected to see your apps, chances are you’ve just switched workspaces, and your programs are still running in a workspace that is now not visible. In many Linux environments, you can switch workspaces by pressing Alt-Ctrl and then an arrow (up, down. left or right). Hopefully, you’ll see your programs still there in another workspace.

Of course, if you happen to like workspaces (many people do), then you have found a useful default feature in Linux.

Settings

Many Linux graphical environments also have some type of settings program or settings panel that let you configure settings on the machine. Note that similarly to Windows and MacOS, things in Linux can be configured in fine detail, and not all of these detailed settings can be found in the settings program. These settings, though, should be enough for most of the things you’ll need to set on a typical desktop system, such as selecting the desktop wallpaper, changing how long before the screen goes blank, and connecting to printers, to name a few.

The settings presented in the application will usually not be grouped the same way or named the same way they are on Windows or MacOS. Even different graphical interfaces in Linux can present settings differently, which may take time to adjust to. Online search, of course, is a great place to search for answers on how to configure things in your graphical environment.

Applications

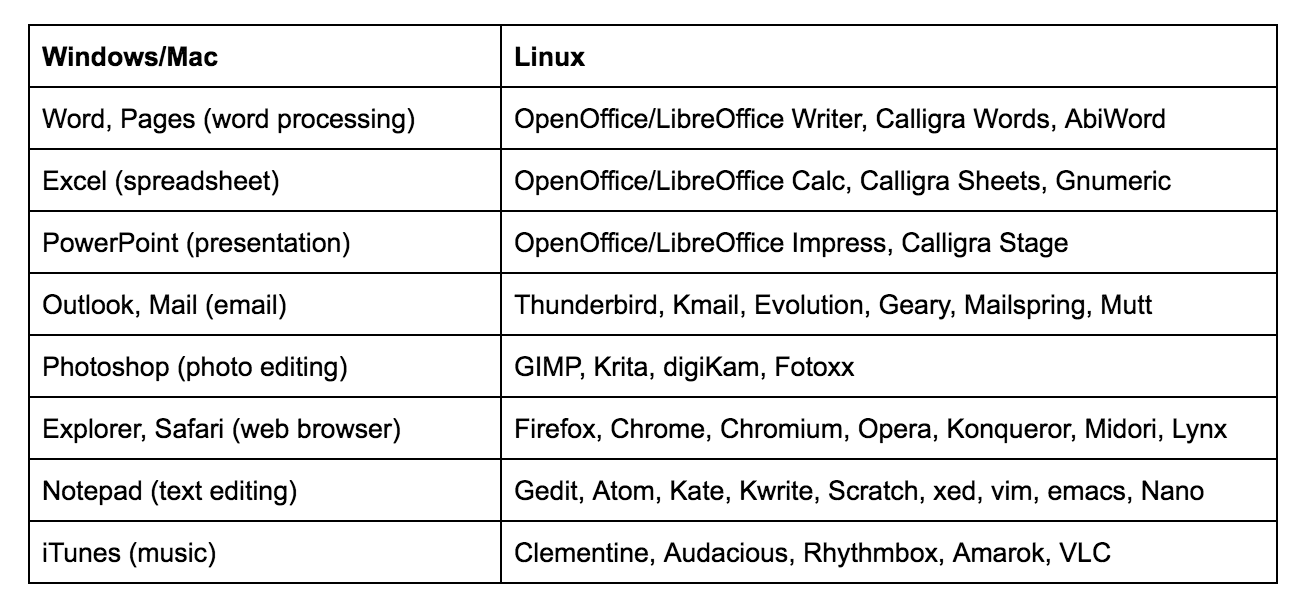

Finally, applications in Linux might be different. You will likely find some familiar applications but others may be completely new to you. For example, you can find Firefox, Chrome, and Skype on Linux. If you can’t find a specific app, there’s usually an alternative program you can use. If not, you can run many Windows applications in a compatibility layer called WINE.

On many Linux graphical environments, you can bring up the applications menu by pressing the Windows Logo key on the keyboard. In others, you need to click on a start/home button or click on an applications menu. In many of the graphical environments, you can search for an application by category rather than by its specific name. For example, if you want to use an editor program but you don’t know what it’s called, you can bring up the application menu and enter “editor” in the search bar, and it will show you one or more applications that are considered editors.

To get you started, here is a short list of a few applications and potential Linux alternatives.

Note that this list is by no means comprehensive; Linux offers a multitude of options to meet your needs.

Learn more about Linux through the free “Introduction to Linux” course from The Linux Foundation and edX.