If for some reason you have decided to comprehend the asynchronous part of Python, welcome to our “Asyncio How-to”.

Note: you can successfully use Python without knowing that asynchronous paradigm even exists. However, if you are interested in how things work under the hood, asyncio is absolutely worth checking.

What Asynchronous is All About?

In a classic sequential programming, all the instructions you send to the interpreter will be executed one by one. It is easy to visualize and predict the output of such a code. But…

Say you have a script that requests data from 3 different servers. Sometimes, depending on who knows what, the request to one of those servers may take unexpectedly too much time to execute. Imagine that it takes 10 seconds to get data from the second server. While you are waiting, the whole script is actually doing nothing. What if you could write a script that could instead of waiting for the second request, simply skip it and start executing the third request, then go back to the second one, and proceed from where it left. That’s it. You minimize idle time by switching tasks.

Still, you don’t want to use an asynchronous code when you need a simple script, with little to no I/O.

One more important thing to mention is that all the code is running in a single thread. So if you expect that one part of the program will be executed in the background while your program will be doing something else, this won’t happen.

Getting Started

Here are the most basic definitions of asyncio main concepts:

-

Coroutine — generator that consumes data, but doesn’t generate it. Python 2.5 introduced a new syntax that made it possible to send a value to a generator. I recommend checking David Beazley “A Curious Course on Coroutines and Concurrency” for a detailed description of coroutines.

-

Tasks — schedulers for coroutines. If you check a source code below, you’ll see that it just says

event_loopto run its_stepas soon as possible, meanwhile_stepjust calls next step of coroutine.

class Task(futures.Future):

def __init__(self, coro, loop=None):

super().__init__(loop=loop)

...

self._loop.call_soon(self._step)

def _step(self):

...

try:

...

result = next(self._coro)

except StopIteration as exc:

self.set_result(exc.value)

except BaseException as exc:

self.set_exception(exc)

raise

else:

...

self._loop.call_soon(self._step)

- Event Loop — think of it as the central executor in asyncio.

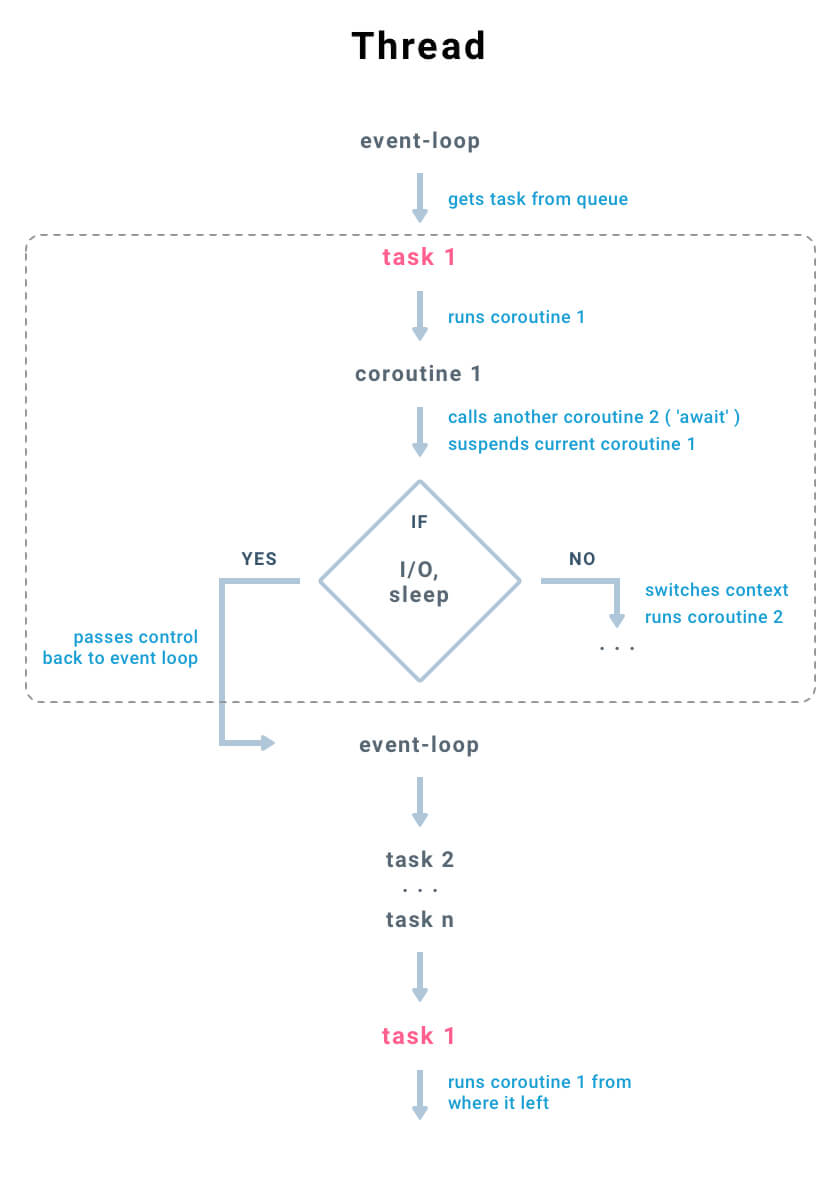

As you can see from the chart:

- The event loop is running in a thread

- It gets tasks from the queue

- Each task calls next step of a coroutine

- If coroutine calls another coroutine (

await <coroutine_name>), current coroutine gets suspended and context switch occurs. Context of the current coroutine(variables, state) is saved and context of a called coroutine is loaded - If coroutine comes across a blocking code(I/O, sleep), the current coroutine gets suspended and control is passed back to the event loop

- Event loop gets next tasks from the queue 2, …n

- Then the event loop goes back to task 1 from where it left

Asynchronous vs Synchronous Code

Let’s try to prove that asynchronous approach really works. I will compare two scripts, that are nearly identical, except the sleep method. In the first one I am going to use a standard time.sleep, and in the second one — asyncio.sleep

Here we use synchronous sleep inside async code:

import asyncio

import time

from datetime import datetime

async def custom_sleep():

print('SLEEP', datetime.now())

time.sleep(1)

async def factorial(name, number):

f = 1

for i in range(2, number+1):

print('Task {}: Compute factorial({})'.format(name, i))

await custom_sleep()

f *= i

print('Task {}: factorial({}) is {}n'.format(name, number, f))

start = time.time()

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

tasks = [

asyncio.ensure_future(factorial("A", 3)),

asyncio.ensure_future(factorial("B", 4)),

]

loop.run_until_complete(asyncio.wait(tasks))

loop.close()

end = time.time()

print("Total time: {}".format(end - start))

Output:

Task A: Compute factorial(2)

SLEEP 2017-04-06 13:39:56.207479

Task A: Compute factorial(3)

SLEEP 2017-04-06 13:39:57.210128

Task A: factorial(3) is 6

Task B: Compute factorial(2)

SLEEP 2017-04-06 13:39:58.210778

Task B: Compute factorial(3)

SLEEP 2017-04-06 13:39:59.212510

Task B: Compute factorial(4)

SLEEP 2017-04-06 13:40:00.217308

Task B: factorial(4) is 24

Total time: 5.016386032104492

Now the same code, but with the asynchronous sleep method:

import asyncio

import time

from datetime import datetime

async def custom_sleep():

print('SLEEP {}n'.format(datetime.now()))

await asyncio.sleep(1)

async def factorial(name, number):

f = 1

for i in range(2, number+1):

print('Task {}: Compute factorial({})'.format(name, i))

await custom_sleep()

f *= i

print('Task {}: factorial({}) is {}n'.format(name, number, f))

start = time.time()

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

tasks = [

asyncio.ensure_future(factorial("A", 3)),

asyncio.ensure_future(factorial("B", 4)),

]

loop.run_until_complete(asyncio.wait(tasks))

loop.close()

end = time.time()

print("Total time: {}".format(end - start))

Output:

Task A: Compute factorial(2)

SLEEP 2017-04-06 13:44:40.648665

Task B: Compute factorial(2)

SLEEP 2017-04-06 13:44:40.648859

Task A: Compute factorial(3)

SLEEP 2017-04-06 13:44:41.649564

Task B: Compute factorial(3)

SLEEP 2017-04-06 13:44:41.649943

Task A: factorial(3) is 6

Task B: Compute factorial(4)

SLEEP 2017-04-06 13:44:42.651755

Task B: factorial(4) is 24

Total time: 3.008226156234741

As you can see, the asynchronous version is 2 seconds faster. When async sleep is used (each time we call await asyncio.sleep(1)), control is passed back to the event loop, that runs another task from the queue(either Task A or Task B).

In a case of standard sleep – nothing happens, a thread just hangs out. In fact, because of a standard sleep, current thread releases a python interpreter, and it can work with other threads if they exist, but it is another topic.

Several Reasons to Stick to Asynchronous Programming

Companies like Facebook use asynchronous a lot. Facebook’s React Native and RocksDB think asynchronous. How do think it is possible for, let’s say, Twitter to handle more than five billion sessions a day?

So, why not refactor the code or change the approach so that software could work faster?