One of the most basic tasks in Linux is setting file permissions. Understanding how this is done should be considered a must-know, first step in your travels through the Linux ecosystem. As you might expect, such a fundamental issue within the operating environment hasn’t changed much over the years. In fact, the Linux file permission system is taken directly from the UNIX file permission (and even uses many of the same tools).

But, don’t think for a second that understanding file permissions is something you’ll wind up having to spend days and days studying…it’s actually quite simple. Let’s walk through what you need to know and how to put it all together.

The Bits and Pieces

The first thing you need to understand is what file permissions apply to. Effectively what you do is apply a permission to a group. When you break it down, the concept really is that simple. But what are the permissions and what are the groups?

There are three types of permissions you can apply:

-

read — gives the group permission to read the file (indicated with r)

-

write — gives the group permission to edit the file (indicated with w)

-

execute — gives the group permission to execute (run) the file (indicated with x)

To better explain how this is applied to a group, you could, for example, give a group permission to read and write to a file, but not execute the file. Or, you could give a group permission to read and execute a file, but not write to a file. You can even give a group full permission to read, write, and execute a file or strip a group of any access to a file by removing all permissions.

Now, what are the groups? There are four:

-

user — the actual owner of the file

-

group — users in the file’s group

-

others — other users not in the file’s group

-

all — all users

For the most part, you will only really ever bother with the first three groups. The all group is really only used as a shortcut (I’ll explain later).

So far so simple, right? Let’s layer on a bit of complexity.

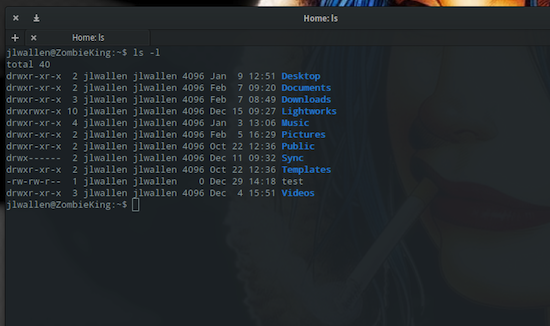

If you open up a terminal window and issue the command ls -l, you will see a line-by-line listing of all files and folders within the current working directory (Figure 1 above).

If you look in the far left column, you’ll notice listings like -rw-rw-r–.

That listing should actually be looked at like so:

rw- rw- r--

As you can see, the listing is broken into three sections:

-

rw-

-

rw-

-

r–

The order is quite important…for both permissions and for groups. The order is always:

-

User Group Others — for groups

-

Read Write Execute — for permissions

In our permissions listing example above, the User has read/write permission, the Group has read/write permission, and Others has only read permission. Had any of those groups been given executable permissions, it would have been represented with an x.

Numerical Equivalent

Let’s make this even more complex. Each permission can also be represented by a number. The numbers are:

-

Read — 4

-

Write — 2

-

Execute — 1

The numerical substitution isn’t an apples to apples change. You can’t drop in:

-42-42-4--

Instead, what you do is add up the numbers you want for each group. Let’s stick with our example above (-rw-rw-r—). To give the User group read and write permission, you would add up 4+2 to get 6. For the Group, you need the same permissions, so they get the same number. You only want Others to have read permissions, so they get 4. The numerical equivalent is now:

664

So, if you want to give a file 664 permissions, you’d issue the chmod command like this:

chmod 664 FILENAME

where FILENAME is the name of the file.

Changing Permissions

Now that you understand the actual permissions of files, it’s time to learn how to change those permissions. This is done with the chmod command. One of the first things you must understand is that, to be able to change the permissions of a file, either you must be the owner of the file or you must have permission to edit the file (or have admin access by way of su or sudo). Because of that, you cannot just jump around in the directory structure and change permissions of files at will.

Let’s stick with our example (-rw-rw-r–). Suppose this file (we’ll name it script.sh) is actually a shell script and needs to be executed…but you only want to give yourself permission to execute that script. At this point, you should be thinking, “Ah, then I need the permission listing to read -rwx-rw-r–!”. To get that x bit in there, you’d run the chmod command like so:

chmod u+x script.sh

At this point, the listing will be -rwx-rw-r–.

If you wanted to give both User and Group executable permission, the command would look like:

chmod ug+x script.sh

See how this works? Let’s make it interesting. Say, for whatever reason, you accidentally give all groups executable permissions for that file (so the listing looks like -rwx-rwx-r-x). If you want to strip Others of executable permissions, issue the command:

chmod o-x script.sh

What if you want to completely remove executable permission from the file? You can do that two ways:

chmod ugo-x script.sh

or

chmod a-x script.sh

That’s where all comes into play. This is used to make the process a bit more efficient. I prefer to avoid using a as it could lead to issues (such as, when you accidentally issue the command chmod a-rwx script.sh).

Directory Permissions

You can also execute the chmod command on a directory. When you create a new directory as a user, it is typically created with the following permissions:

drwxrwxr-x

NOTE: The leading d indicates it is a directory.

As you can see, both User and Group have executable permission for the folder. This does not mean that any files created in the folder will have the same permissions (files will be created with the default system permissions of -rw-rw-r–). But, suppose you do create files in this new directory, and you want to strip Group of write permissions. You don’t have to change into the directory and then issue the chmod command on all the files. You can add the R option (which means recursive) to the chmod command and change the permission on both the folder and all the containing files.

Now, suppose our example is a folder named TEST and within it is a number of scripts — all of which (including the TEST folder) have permissions -rwxrwxr-x. If you want to strip Group of write permissions, you could issue the command:

chmod -R g-w TEST

If you now issue the command ls -l, you will see the TEST folder now has a permission listing of drwxr-xr-x. Group has been stripped of its write permissions (as will all the files within).

Permission to Conclude

At this point, you should now have a solid understand of the basic Linux file permissions. There are more advanced issues that you can now easily study, such as setuid and setgid and ACLs. Without a good foundation of the basics, however, you’d quickly get lost with those next-level topics.

Linux file permissions haven’t changed much, since the early days. And, they most likely won’t change much going into the future.