With all the attention you are seeing on Linux and its use on the Internet and in devices like Arduino, Beagle, and Raspberry Pi boards and more, perhaps you are thinking it’s time to try it out. This series will help you successfully make the transition to Linux. If you missed the earlier articles in the series, you can find them here:

Part 2 – Disks, Files, and Filesystems

Part 3 – Graphical Environments

Installing software

To get new software on your computer, the typical approach used to be to get a software product from a vendor and then run an install program. The software product, in the past, would come on physical media like a CD-ROM or DVD. Now we often download the software product from the Internet instead.

With Linux, software is installed more like it is on your smartphone. Just like going to your phone’s app store, on Linux there is a central repository of open source software tools and programs. Just about any program you might want will be in a list of available packages that you can install.

There isn’t a separate install program that you run for each program. Instead you use the package management tools that come with your distribution of Linux. (Remember a Linux distribution is the Linux you install such as Ubuntu, Fedora, Debian, etc.) Each distribution has its own centralized place on the Internet (called a repository) where they store thousands of pre-built applications for you to install.

You may note that there are a few exceptions to how software is installed on Linux. Sometimes, you will still need to go to a vendor to get their software as the program doesn’t exist in your distribution’s central repository. This typically is the case when the software isn’t open source and/or not free.

Also keep in mind that if you end up wanting to install a program that is not in your distribution’s repositories, things aren’t so simple, even if you are installing free and open source programs. This post doesn’t get into these more complicated scenarios, and it’s best to follow online directions.

With all the Linux packaging systems and tools out there, it may be confusing to know what’s going on. This article should help clear up a few things.

Package Managers

Several packaging systems to manage, install, and remove software compete for use in Linux distributions. The folks behind each distribution choose a package management system to use. Red Hat, Fedora, CentOS, Scientific Linux, SUSE, and others use the Red Hat Package Manager (RPM). Debian, Ubuntu, Linux Mint, and more use the Debian package system, or DPKG for short. Other package systems exist as well, while RPM and DPKG are the most common.

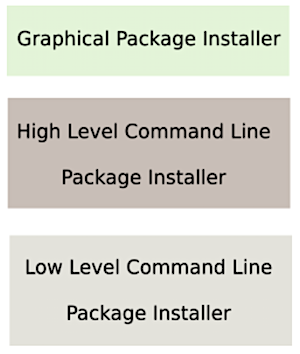

Regardless of the package manager you are using, they typically come with a set of tools that are layered on top of one another (Figure 1). At the lowest level is a command-line tool that lets you do anything and everything related to installed software. You can list installed programs, remove programs, install package files, and more.

This low-level tool isn’t always the most convenient to use, so typically there is a command line tool that will find the package in the distribution’s central repositories and download and install it along with any dependencies using a single command. Finally, there is usually a graphical application that lets you select what you want with a mouse and click an ‘install” button.

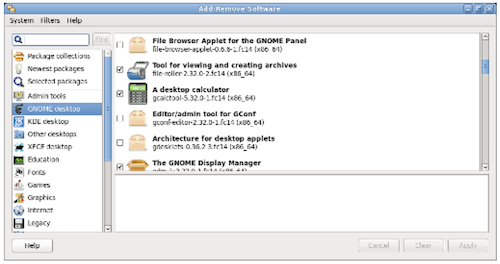

For Red Hat based distributions, which includes Fedora, CentOS, Scientific Linux, and more, the low-level tool is rpm. The high-level tool is called dnf (or yum on older systems). And the graphical installer is called PackageKit (Figure 2) and may appear as “Add/Remove Software” under System Administration.

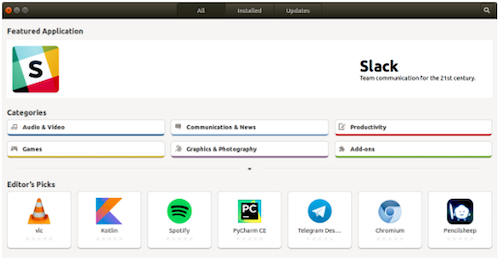

For Debian based distributions, which includes Debian, Ubuntu, Linux Mint, Elementary OS, and more, the low-level, command-line tool is dpkg. The high-level tool is called apt. The graphical tool to manage installed software on Ubuntu is Ubuntu Software (Figure 3). For Debian and Linux Mint, the graphical tool is called Synaptic, which can also be installed on Ubuntu.

You can also install a text-based graphical tool on Debian related distributions called aptitude. It is more powerful than Synaptic, and works even if you only have access to the command line. You can try that one if you want access to all the bells and whistles, though with more options, it is more complicated to use than Synaptic. Other distributions may have their own unique tools.

Command Line

Online instructions for installing software on Linux usually describe commands to type in the command line. The instructions are usually easier to understand and can be followed without making a mistake by copying and pasting the command into your command line window. This is opposed to following instructions like, “open this menu, select this program, enter in this search pattern, click this tab, select this program, and click this button,” which often get lost in translation.

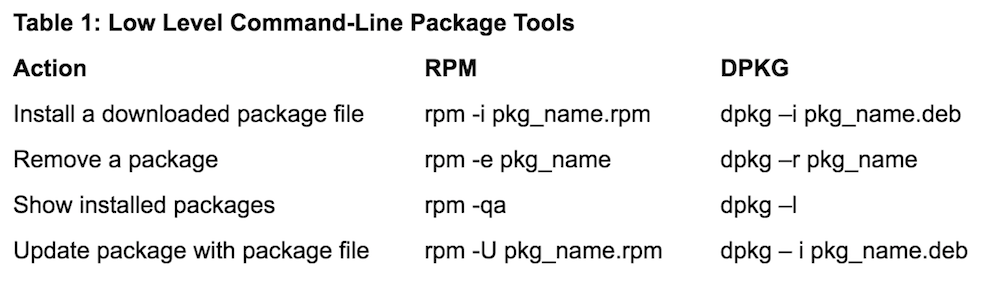

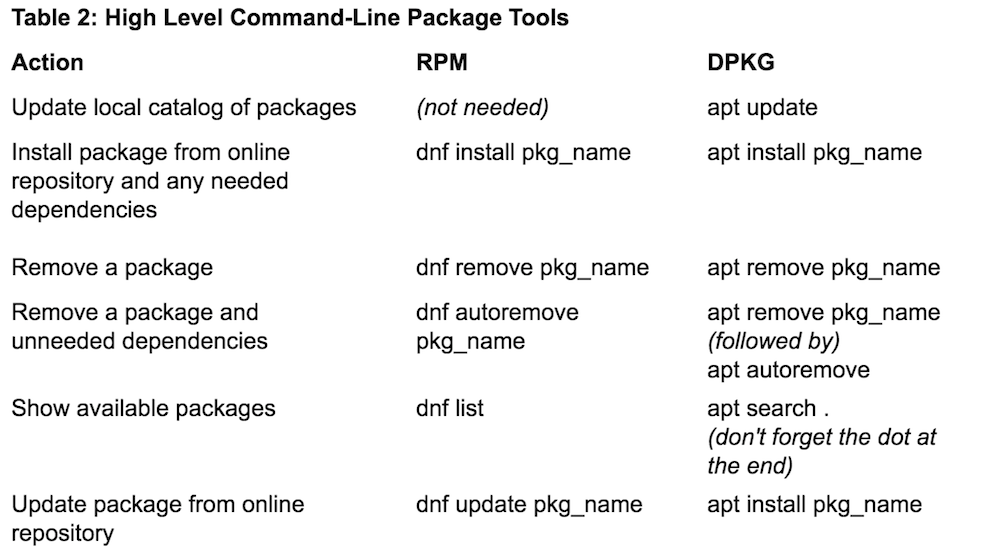

Sometimes the Linux installation you are using doesn’t have a graphical environment, so it’s good to be familiar with installing software packages from the command line. Tables 1 and 2 a few common operations and their associated commands for both RPM and DPKG based systems.

Note that SUSE, which uses RPM like Redhat and Fedora, doesn’t have dnf or yum. Instead, it uses a program called zypper for the high-level, command-line tool. Other distributions may have different tools as well, such as, pacman on Arch Linux or emerge on Gentoo. There are many package tools out there, so you may need to look up what works on your distribution.

These tips should give you a much better idea on how to install programs on your new Linux installation and a better idea how the various package methods on your Linux installation relate to one another.

Learn more about Linux through the free “Introduction to Linux” course from The Linux Foundation and edX.